- A-

- A

- A+

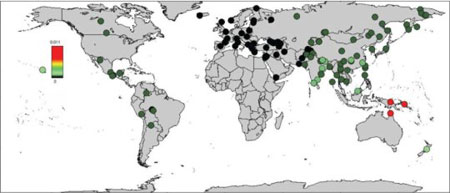

A world map of Neanderthal and Denisovan ancestry in modern humans

Most non-Africans possess at least a little bit Neanderthal DNA. But a new map of archaic ancestry suggests that many bloodlines around the world, particularly of South Asian descent, may actually be a bit more Denisovan, a mysterious population of hominids that lived around the same time as the Neanderthals. The analysis also proposes that modern humans interbred with Denisovans about 100 generations after their trysts with Neanderthals.

Most non-Africans possess at least a little bit Neanderthal DNA. But a new map of archaic ancestry-published March 28 in Current Biology - suggests that many bloodlines around the world, particularly of South Asian descent, may actually be a bit more Denisovan, a mysterious population of hominids that lived around the same time as the Neanderthals. The analysis also proposes that modern humans interbred with Denisovans about 100 generations after their trysts with Neanderthals.

The Harvard Medical School/UCLA research team that created the map also used comparative genomics to make predictions about where Denisovan and Neanderthal genes may be impacting modern human biology. While there is still much to uncover, Denisovan genes can potentially be linked to a more subtle sense of smell in Papua New Guineans and high-altitude adaptions in Tibetans. Meanwhile, Neanderthal genes found in people around the world most likely contribute to tougher skin and hair.

The results showed that individuals from Oceania possess the highest percentage of archaic ancestry and south Asians possess more Denisovan ancestry than previously believed. This reveals previously unknown interbreeding events, particularly in relation to Denisovans. In contrast, Western Eurasians are the non-Africans least likely to have Neanderthal or Denisovan genes. "The interactions between modern humans and archaic humans are complex and perhaps involved multiple events."

Similar News

Links

Elm TV

Elm TV

Photo

Photo

Video

Video